Written by: Lawyer Shao Jiadian

Introduction

In the past few years, the words 'issuing tokens' have become the most sensitive terms in the Web3 world. Some have become famous overnight because of it, while others have been investigated, had their tokens returned, or had their accounts banned. The issue is not in 'issuing,' but in 'how to issue.' While some tokens are listed on mainstream exchanges and have communities and DAOs, others are deemed illegal securities. The distinction lies in whether they are issued within the legal framework.

The reality of 2025 is that utility tokens are no longer a gray area. Regulation is scrutinizing every TGE, every SAFT, and every airdrop with a magnifying glass.

This article is written for every Web3 project founder: On the road from Testnet to DAO, the legal structure is the skeleton of your project. Before issuing tokens, learn to build the skeleton first.

Note: This article is based on an international legal perspective and does not target or apply to the legal environment of mainland China.

The 'identity' of tokens is not something you can define by writing a white paper.

Many teams will say: 'Our tokens are just functional, without profit distribution, so it should be fine, right?'

But reality is not so. In the eyes of regulators, the 'identity' of tokens depends on market behavior, not on how you describe it.

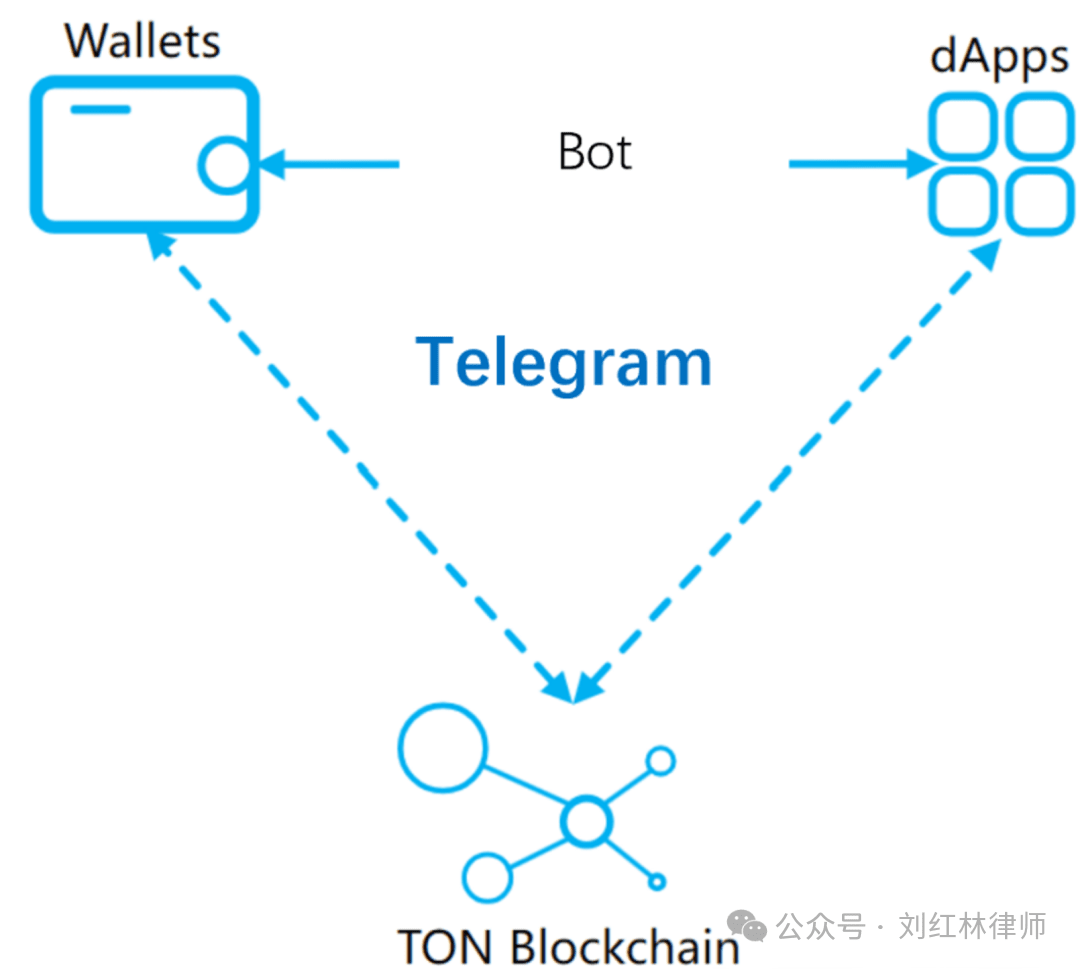

A typical case is Telegram's TON project.

Telegram raised $1.7 billion from investors, claiming that tokens are merely 'fuel' for future communication networks;

But the U.S. SEC believes this financing constitutes an unregistered securities offering—because the purpose of the investors' purchase is clearly for 'future appreciation,' rather than 'immediate use.'

The result was that Telegram refunded the investment and paid fines, forcing the TON network to operate independently from Telegram.

Lesson: Regulators look at 'investment expectations,' not 'technical visions.' As long as you use investors' money to build an ecosystem, it carries securities attributes.

Therefore, do not fantasize about using 'functional' labels to eliminate risks. The nature of tokens is dynamically evolving—early in the project they are investment contracts, and only after the mainnet launch can they potentially become true utility credentials.

First, clarify which type of project you are.

What determines your compliance path is not the token name, nor the total amount, but the project type.

Infrastructure category (Infra):

For example, Layer1, Layer2, public chains, ZK, storage protocols.

Usually adopts 'Fair Launch,' with no pre-mining, no SAFT, and tokens generated by node consensus.

Such as Bitcoin, Celestia, EigenLayer all belong to this category.

The advantages are naturally distributed and have low regulatory risk; the disadvantages are difficult financing and long development cycles.

Application layer projects (App Layer):

For example, DeFi, GameFi, SocialFi.

Tokens are pre-mined (TGE) by the team and lead the ecological treasury, typical representatives include Uniswap, Axie Infinity, Friend.tech.

The business model is clear, but the compliance risk is high: sales, airdrops, and circulation all need to address regulatory disclosures and KYC issues.

Conclusion: Infrastructure survives on consensus, application projects rely on structure for survival. Without a well-designed structure, all 'Tokenomics' are mere talk.

Testnet phase: Do not rush to issue tokens; first build the 'legal skeleton.'

Many teams start looking for investors, signing SAFTs, and pre-mining tokens during the Testnet phase.

But the most common mistake at this stage is:

On one hand, holding investors' money while claiming 'this is just a utility token.'

The U.S. Filecoin serves as a cautionary tale. It raised about $200 million through SAFT before the mainnet launch and although it obtained an SEC exemption, due to delays in launch and tokens being temporarily unavailable, investors questioned its 'securities attributes,' ultimately leading the project to incur huge compliance costs to rectify.

The correct approach is:

Distinguish between two levels of entities:

DevCo (Development Company) is responsible for technical research and development and intellectual property;

Foundation / TokenCo (Foundation or Token Company) is responsible for ecological construction and future governance.

Financing method: using equity + Token Warrant structure, rather than selling tokens directly.

Investors gain the right to future tokens, rather than ready-made token assets.

This approach was first adopted by projects like Solana and Avalanche, allowing early investors to participate in ecological construction while avoiding direct triggering of securities sales.

Principle: The legal structure at the early stage of the project is like the genesis block. If you write the logic wrong once, compliance costs may multiply tenfold.

Mainnet issuance (TGE): The moment most easily monitored by regulators

Once tokens can be traded and have a price, they enter the regulatory radar. Especially when it involves airdrops, LBP (Liquidity Bootstrapping Pool), Launchpad, and other public distributions.

Public chain projects:

For example, Celestia, Aptos, Sui, etc., typically generate tokens automatically by the validator network during TGE.

The team does not directly participate in sales, and the distribution process is decentralized, minimizing regulatory risks.

Application layer projects:

Such as the airdrops of Arbitrum and Optimism, or community distributions of Blur and Friend.tech,

Some regulatory agencies are paying attention to whether their 'distribution and voting incentives constitute a securities sale.'

The safety line during the TGE phase lies in disclosure and usability:

1. Clearly define the use cases and functions of the token;

2. Publicly disclose token allocation ratios, lock-up periods, and unlocking mechanisms;

3. Implement KYC/AML for investors and users;

4. Avoid 'expected returns' type of promotion.

For example, the Arbitrum Foundation clearly stated at TGE: its airdrop is only for governance purposes and does not represent investment or profit rights; and gradually reduced the foundation's leading proportion in community governance—this is precisely the key path to 'de-securitization' of tokens.

DAO phase: Learn to 'let go' and truly decentralize the project.

Many projects end once they 'issue tokens,' but the real challenge is—how to relinquish control and return tokens to a public good.

Taking Uniswap DAO as an example:

Initially led by Uniswap Labs in development and governance;

Later managed by Uniswap Foundation, overseeing the treasury and funding ecological projects;

The community decides on protocol upgrades and parameter adjustments through UNI voting.

This structure makes it harder for regulators to identify as 'centralized issuers' and also increases community trust.

Some projects that did not handle the DAO transition well, such as certain GameFi or NFT ecosystems, are deemed 'pseudo-decentralized' due to the team still controlling the majority of tokens and holding voting rights, thus still facing securities risks.

Decentralization is not 'laissez-faire,' but 'verifiable exit.' Achieving a triangular balance among code, foundation, and community is the safe DAO structure.

What regulators are looking at: Can you prove 'this is not a security'

Regulators are not afraid of you issuing tokens; they are afraid that you say 'it's not a security,' but your actions resemble that of a security.

In 2023, the SEC listed dozens of 'functional tokens' in its lawsuits against Coinbase, Kraken, and Binance.US, identifying that they exhibit characteristics of 'investment contracts' during both the sales and marketing phases. This means that as long as the project conveys 'expected returns' in its token sales, even if the token itself has functionality, it will be regarded as a security.

Therefore, the key to compliance is dynamic response:

Testnet → Focus on technology and development compliance;

TGE → Emphasize use cases and functional attributes;

DAO → Reduce team control and strengthen governance mechanisms.

The risks differ at each stage, and each upgrade requires a reassessment of token positioning. Compliance is not just about stamping documents; it is a continuous iteration.

Conclusion: Projects that traverse cycles do not rely on 'speed,' but on 'stability.'

Many projects fail, not because the technology is inadequate, but because the structure is too poor. While others are still talking about 'price fluctuations,' 'airdrops,' and 'listings,' truly smart founders are already building legal frameworks, writing compliance logic, and planning for DAO transformation.

Issuing functional tokens is not about evading regulation but proving legally that you do not need regulation. When code takes over the rules, the law becomes your firewall.